Familiar Patterns

There’s a moment I've seen show up time and time again in executive meetings.

A piece of work has been commissioned at some point in the past. Time has been spent and money has (or needs to be) moved. An initiative update is in the process of being presented - usually clearly, competently, and with evidence of effort and achievement.

Then, right at the end, someone leans forward to ask a perfectly reasonable question - but one that makes many presenters wince (and not always inwardly). It goes something along the lines of: “So, how are you checking whether this was worth the time and money you invested?”

Sometimes the question comes from curiosity. Sometimes it's from a peer who knows the answer won’t be clean. Sometimes (my personal favourite) it’s the same person who originally supported the work, now wearing a different hat in front of their peers.

The presenter usually responds by talking about what’s been done and what’s been rolled out. Uptake. Completion rates. Early feedback. A few related numbers. Maybe a dashboard or two.

All of it is true and completely defensible.

And yet, there’s an uncomfortable sense from the room that the question hasn’t really been answered, not because nothing improved (things usually have improved in some manner) but because improvement and impact aren’t the same thing. The organisation can show activity. It can show delivery. It might even be able to show movement in some measures. What it struggles to show is whether those changes have materially strengthened the business in a way that justifies the investment and the opportunity cost.

In theory, this should lead to a broader conversation about the impact they want to see, but usually the conversation narrows instead. The focus shifts to what can be reported cleanly, and the moment to explore impact passes.

No one is being deliberately avoidant, but something important has been quietly sidestepped.

Measurement Becomes the Focus

The usual explanation for this sidestep is a technical (and, quite frankly, accurate) one: Impact is hard to measure.

Outcomes are typically longer‑term. The relevant data is messy (if even captured at all). Accountability is unclear. Stakeholders want simple numbers even when reality isn’t simple. So instead, the work becomes about measurement quality: "better" metrics, simpler or more recognisable data, or more frequent reporting.

All of this sounds sensible, but it’s also the point where the opportunity to demonstrate real value leaves the room faster than a teenager being asked to do chores. The problem is framed as solvable without actually changing anything uncomfortable.

An assumption creeps in: if impact isn’t showing up clearly, it's because the reporting just needs sharpening.

The Misalignment Gap

The truth most organisations skirt around is that they are measuring exactly what their systems are designed to reward, which isn't impact - it's activity disguised as "achievement".

What’s missing isn’t data: it’s alignment. Organisations talk about long‑term productivity, resilience, safety, capability, transformation, but when pressure hits, their systems consistently reward something else:

- Short‑term financial performance

- Visible activity and delivery

- Output/action over learning

- Risk containment over long‑term capacity

This isn’t theoretical. It shows up repeatedly when incentives, governance, and decision rights are examined.

Across banking, aviation, energy, and gaming, public inquiries and disclosures have shown the same pattern: stated long‑term goals that have been undermined by short‑term incentive design. Leaders are paid - often generously - for annual financial outcomes, while safety, trust, sustainability, or compliance carry far less weight in practice.

The result isn’t confusion - quite the opposite: it’s coherence, just not with intent.

The standard approach to measurement doesn’t expose this gap. In many cases, it politely papers over it, translating systemic trade‑offs into tidy numbers that feel neutral and objective.

This makes the organisation look busy, disciplined, and data‑driven while quietly reinforcing the very behaviours it claims to be trying to change.

Optimising for Activity Over Outcomes

This pattern doesn’t persist because organisations are naive or insincere. It persists because a series of reasonable decisions, made under pressure, compound in predictable ways.

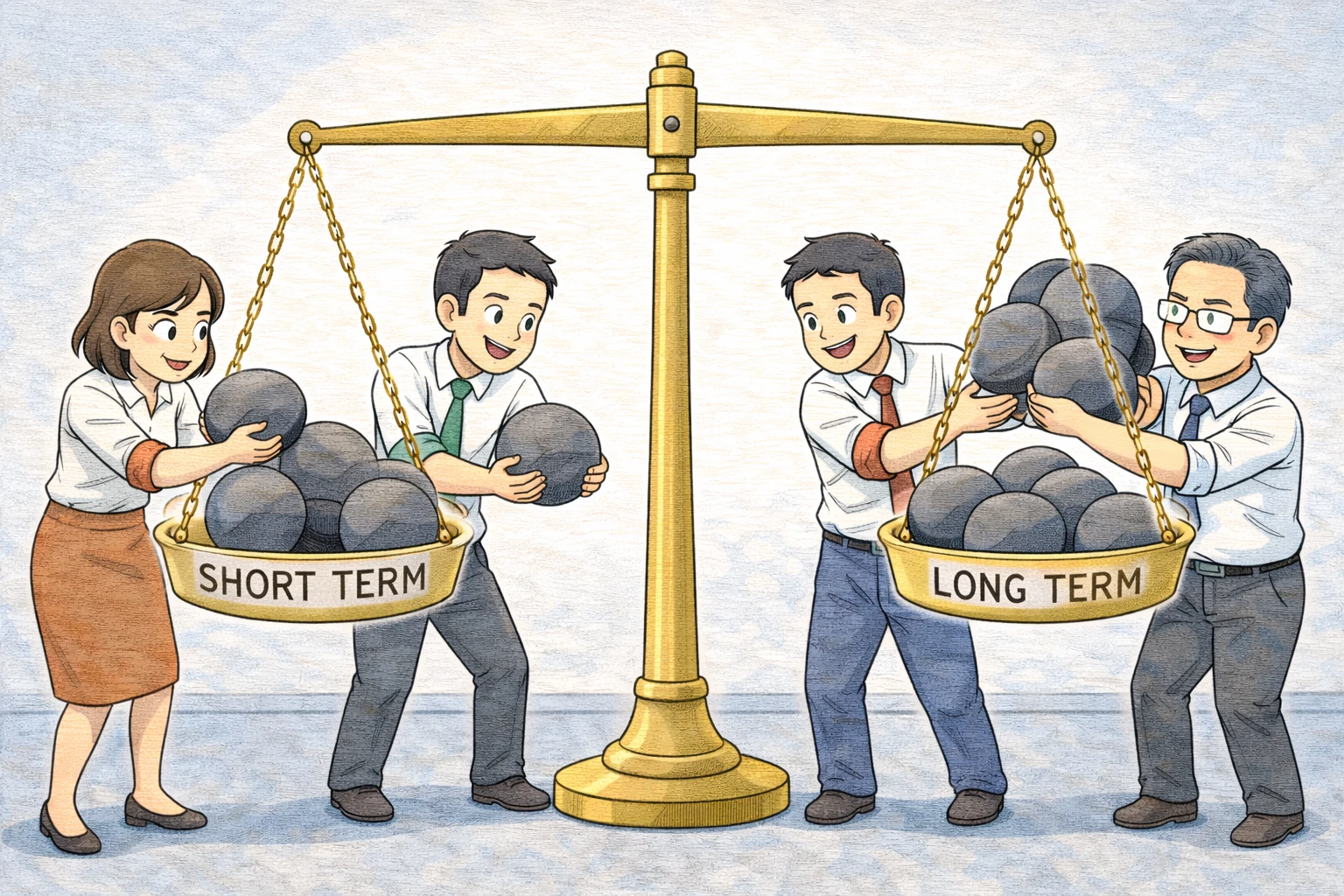

Time horizons shrink as soon as resources are committed. Leaders are asked to justify spend within annual cycles, even when the work is meant to change how the organisation performs over several years.

Accountability follows the same logic. It is far easier to hold people accountable for things they can directly control (milestones hit, programs delivered, participation achieved) than for outcomes that emerge later, through many hands. And let's face it - most leaders prefer to be measured on things they have complete control over.

Trade‑offs, meanwhile, are rarely made explicit. Choosing speed over depth. Visibility over durability. Topicality over system‑level learning or change. These choices are often implicit, not debated, and therefore not owned.

This leads to work being designed in pieces. Initiatives are scoped, funded, and governed as discrete efforts, despite impact being expected to appear at the level of the whole system. The maths doesn’t quite work, but the structure looks tidy on paper. People optimise what they can see, explain, and defend.

Second‑order effects of these choices arrive later. By then, roles have changed, priorities have shifted, or attention has moved on. The outcomes are real, but the accountability is... diffuse.

If or when dissatisfaction with the success of the initiative eventually surfaces, it’s tempting to treat it as a measurement failure.

In reality, it’s usually a delayed signal from the design choices already made.

Losing Clarity by Compressing Complexity

Most organisations try to connect to impact in ways that feel entirely sensible.

They elevate the narrative. Introduce structured reporting. Build enterprise scorecards. Limit each initiative to contributing one or two measures to a broader framework - sometimes stretching a single metric far beyond what it was ever designed to explain.

None of this is misguided. In many cases, it’s the only move that feels immediately available.

However, these responses sit downstream of the real issue. They make activity easier to explain without changing what the organisation is actually optimised to produce.

What eventually surfaces isn’t outright failure. It’s something quieter: a sense that a lot is happening, yet it’s still unclear whether anything materially changed. That signal shouldn’t be dismissed. It’s often the first hint that the issue isn’t measurement - it’s design.

Designing For Outcomes

If impact is a property of the system, not a feature of individual programs, then the implications are uncomfortable but grounding.

The work isn’t to find the perfect indicator: it’s to be clearer about intent, and more honest about the consequences of how work is designed.

That means spending less time debating measures in isolation, and more time surfacing the trade‑offs the organisation is actually making: between short‑term performance and long‑term capacity, between control and learning, between speed and resilience.

It means asking whether the outcomes being sought are plausible given the way authority, incentives, and attention are currently structured.

And it means accepting that some ambiguity can’t be measured away. It has to be managed through judgment, not dashboards.

This kind of work is slower. It doesn’t always produce neat artefacts. But it tends to move the conversation closer to where impact is really created or constrained.

Most impact measurement efforts don’t fail because organisations lack data, effort, or technical skill. They fail because measurement is being asked to compensate for misalignment elsewhere in the system - to demonstrate value that the system itself was not designed to reliably produce. This tension shows up repeatedly in the work I’ve done with leadership teams in the past.

Until intent, work design, and reward systems are brought into closer alignment, better metrics won’t resolve this issue.

They’ll simply make it easier to explain why the organisation is busy without being sure it’s becoming better.